The Virginia House frame takes its first steps upward from the ground in the historic trades carpenters yard at Colonial Williamsburg under a cover of the new year’s snow.

And suddenly you know: It's time to start something new and trust the magic of beginnings.

Meister Eckhart

Good new year dear friends!

One hundred and three days ago, we began this journal account of our Virginia House Project. After five-years of forbidden fireplaces and minimum footprints and rampaging pandemics across the continent from west to east and north to south, it appeared to us then we had at last begun in earnest.

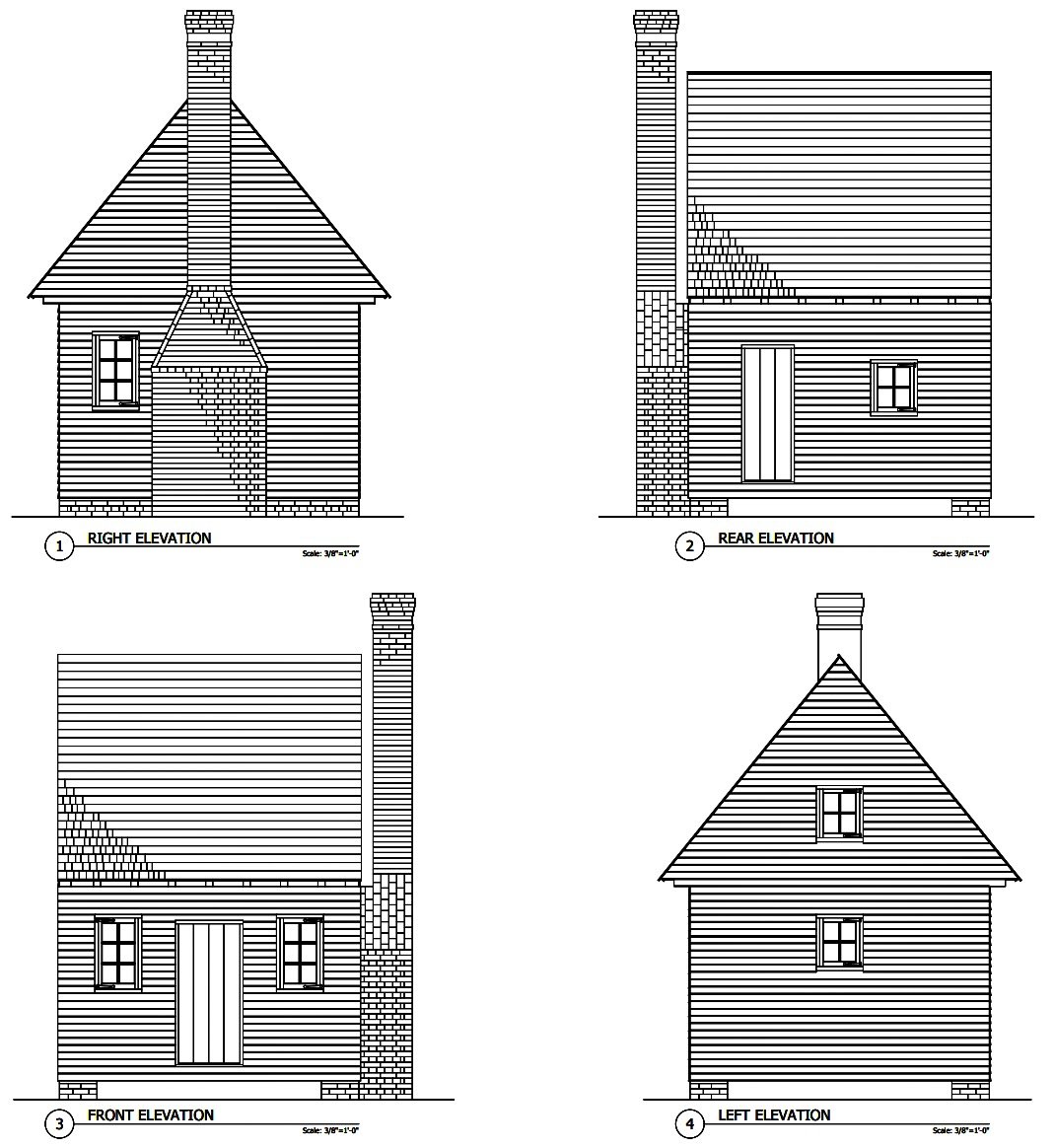

And so it has proved. We began back in September with the example of the Chesapeake’s oldest surviving one-room Virginia Frame House, “Pear Valley” as it is known. Pear Valley must be one of the most thoroughly studied houses per-square-foot in the country, yet I cannot find a single case where it has been reconstructed in an experimental manner. Our model was adapted and refined by architectural historian Jeff Klee through a succession of meticulous designs in consultation with our architects David Stemann and Ed Pease. After many changes and most of three months, the plans were done and perfect.

As detailed specifications became available, Gloucester sawyer Ryan Penner volunteered to provide the framing members. As requested, he skillfully milled the many timbers required from the leanest possible trees, sometimes being compelled to cut so close as to leave long corners still deep in bark. The result was three truck loads of mostly very regular timbers, yet none ever far from the edge of “Beautiful Necessity.”

Those cut timbers were then delivered into the charge of project carpenter Matt Sanbury and his crew, who sorted them into “wany” (as in “going away” at the edges), full, and best, and assigned them accordingly to positions inside or outside, public or private, candle-level or up in the dark.

Our Virginia House is Matt’s journeyman project, and it is a challenging one. Not only are our timbers cut close to the bark, and the 17th century framing method unfamiliar and complex, but the structural members are to be left largely exposed, as they would no longer have been in the 18th century period for which Matt is trained. Our countryman’s frame requires skills almost lost even to the age of old Williamsburg.

Overseeing everything with his benevolent eye is master carpenter Garland Wood. This is Garland’s last frame, concluding forty years as an historic trades carpenter at Colonial Williamsburg. Yet it is his first proper “yeoman’s house,” the sort of modest dwelling that would have been common throughout the Chesapeake region in the first century after the Jamestown landing. So it is Garland’s first time working with such early details as clasped purlins and chamfered corners and lamb’s tongue stops. Such little refinements seem trivial to us now only because we do not labor in the field or cut our own wood or grow our own food. They would have been the pride and elevation of the humble farmer once.

All that work and all those considerations combined to stretch our Virginia Frame out across the ground on oak sills and floor joists just as the year closed. Now, in the new year, our frame takes a new direction and begins to rise on pine posts and plates and rafters. Lowly though it certainly remains to the passing eye, to me after all this while, it almost seems to be taking flight.

Spes in Caelis, Pes in Terris

“Hope in heaven, feet on the ground,” as the old saying goes. To what end do we lay down our foundations and raise up our house? To regain our footing and reach up toward the sky. To raise up our minds from the solid earth. To recapture the magic of beginnings.

Yours in all good hope,

Michael

The Innermost House Foundation is an entirely volunteer organization dedicated to renewing transcendental values for our age.

IMAGES

M. Lorence: Carpenters Yard Under Snow

Jeffrey Klee: Virginia House Plans

D. Lorence: Dovetail Joint Pocket

M. Lorence: Virginia Frame Under Snow

QUOTATIONS

”And suddenly you know. . .” Meister Eckhart