There are moments when we all, in one way or another, have to go to a place that we have never seen, and do what we have never done before.

Karen Armstrong, A Short History of Myth

I have been away from writing for a year, away and among those friends who daily go on making the pursuit of our “dream too wild” a practical reality. With each passing week, the Virginia House Project leads into deeper relation with our ground-truthing and truth-telling exercise. It is more and more difficult to tell the truth across the space that separates our expectations from the realities we encounter. We struggle to remember a lost attitude of life. We have been away in the Land that Time Forgot.

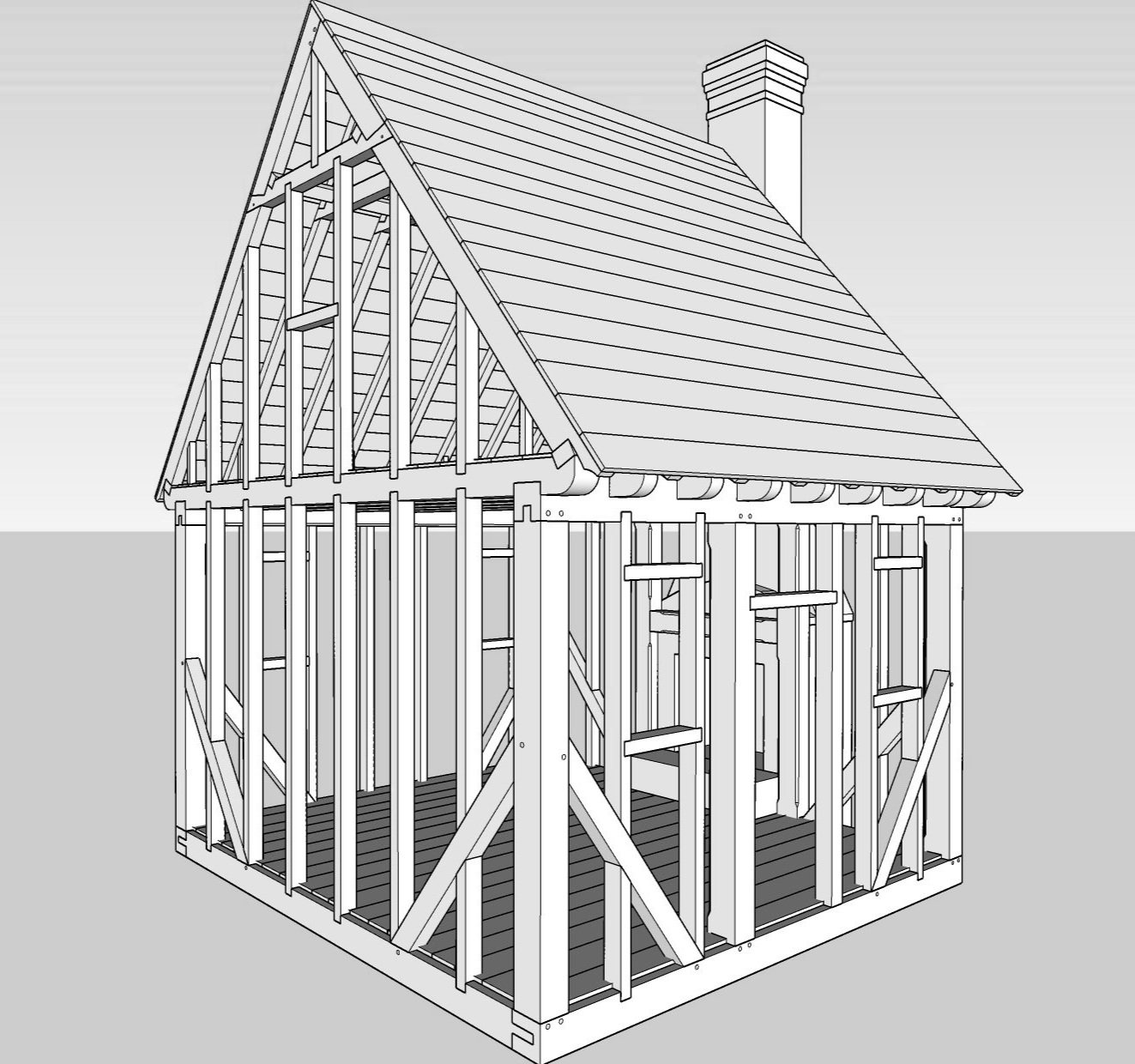

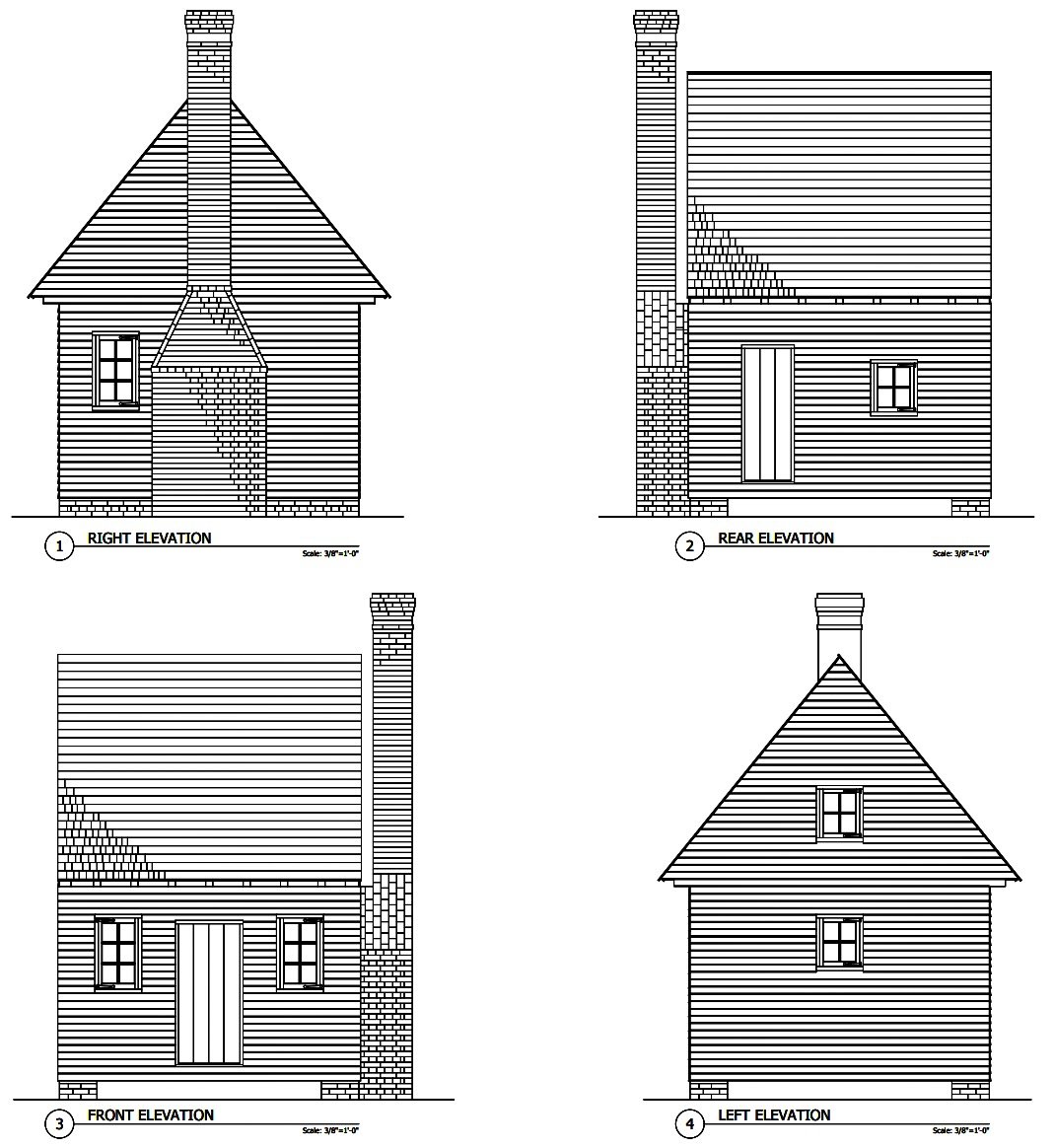

We have been rained on and washed out and buried so deep in clay and mud it threatened to interrupt six years of slow progress. We have been pulled out and picked up and borne across a field in a kindly farmer’s truck. We have had truckloads of rock dumped in our path. We have labored to dig holes so clotted with old roots that it sometimes seemed we must either surrender to broken shovels or perish to go on. We have carried water and cut trees. We have calculated the cast of the sun and found ourselves confounded by cloudy days. We have made war on white mold and on black mold. We have reshaped our project around the holiness of mother-love, the banality of smoke detectors, the weight of half a gross of bricks. We have been rescued by tender mercies and generosities without end.

When did all this begin? Perhaps it goes back to the forests of our first beginnings. Or nearer, to the woods of our remembered forebears, to the timbered houses of our ancestors in this land. Or nearer still, to that time twelve years ago when fate stole us away from our Life in the Woods. I no longer know how to mark the years and days. I count time in the kindnesses of friends.

My dear friend Allen Harding is the son of Walter Harding, the last century’s great scholar of Henry Thoreau, and founder of the Thoreau Society eighty years ago. That is Walter there in that canoe. Ah, the summer memories!

Allen and I met nine years ago at the Annual Gathering of the Thoreau Society. We have travelled half the country together since then, ever in search of a place to land our dream of regaining that Thoreauvian paradise we all left behind in California. Nine years can seem an eternity away from paradise. It is time enough to know a true friend.

I well remember when Allen called me one day from the car on his way home from yet another long, place-searching trip to Virginia. Allen is a tireless explorer of new places, and that day he had steered a circumnavigating course west on his way back north to New York. Somewhere he boarded a boat and crossed over to the Other Side. “Michael,” Allen said, “I have found the land that time forgot.”

That was four years ago now. From that day to this, we have labored together to bring this dream to renewal, else it be truly lost. How do you regain the timeless past to the timely present? How do you secure its future? Allen Harding, Michael Frederick, Jeff Klee, David Stemann and Ed Pease, Garland Wood and Matt Sanbury, Ryan Penner, Cliff Williams, John Smith, and many other generous friends. How do you thank such companions of the soul through this embodied life? We have unearthed things about this land in which we all live that would hardly yield to any but our singular course of digging. We have dug up a past world that illuminates the present, and perchance the human future.

A year ago, at the far end of what we thought to be a settled path, we found ourselves in a dark wood, “for the straight way was lost to us.” We encountered such sudden and unforseeable obstacles in the path we had so long pursued that for awhile they seemed impassible. There was no way to go forward but to go around. It has been a long way around.

But obstacles can sometimes prove a blessing if they compel you down less-traveled roads you were powerless to choose, but needed to explore. So it has proved for us. We have not merely learned what we needed to learn. We have gone where we needed to go. We have changed what we needed to change. We have done what we needed to do.

Now, twelve long months later, we find ourselves where I never expected to be. But then, I have never known where we were going. It is important, I suppose, to imagine you know where you are going from day to day, just in order to go on. But perhaps it is even perilous to be proved right for too long. Necessity wants a hand in where we go and what we are. “Let us build altars to Beautiful Necessity.”

A hundred hands and a thousand blessings have brought us to this place of beautiful repose. Sic itur ad astra. Thus we journey to the stars.

And all shall be well, and all shall be well, and all manner of thing shall be well.

Farewell!

Michael

IMAGES

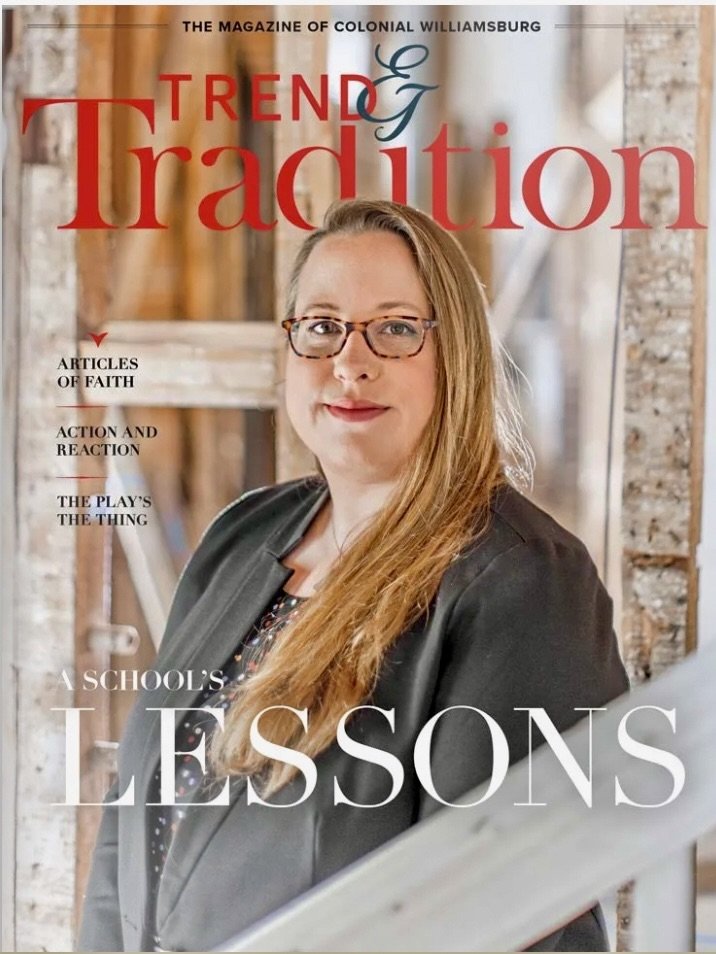

It’s All About the Details, by Through J’s Lens

Another Broken Shovel, March 2022, by M. Lorence

Walter Harding, Thoreau Digital Commons

Forest Landscape in Fog, by Ianachyva

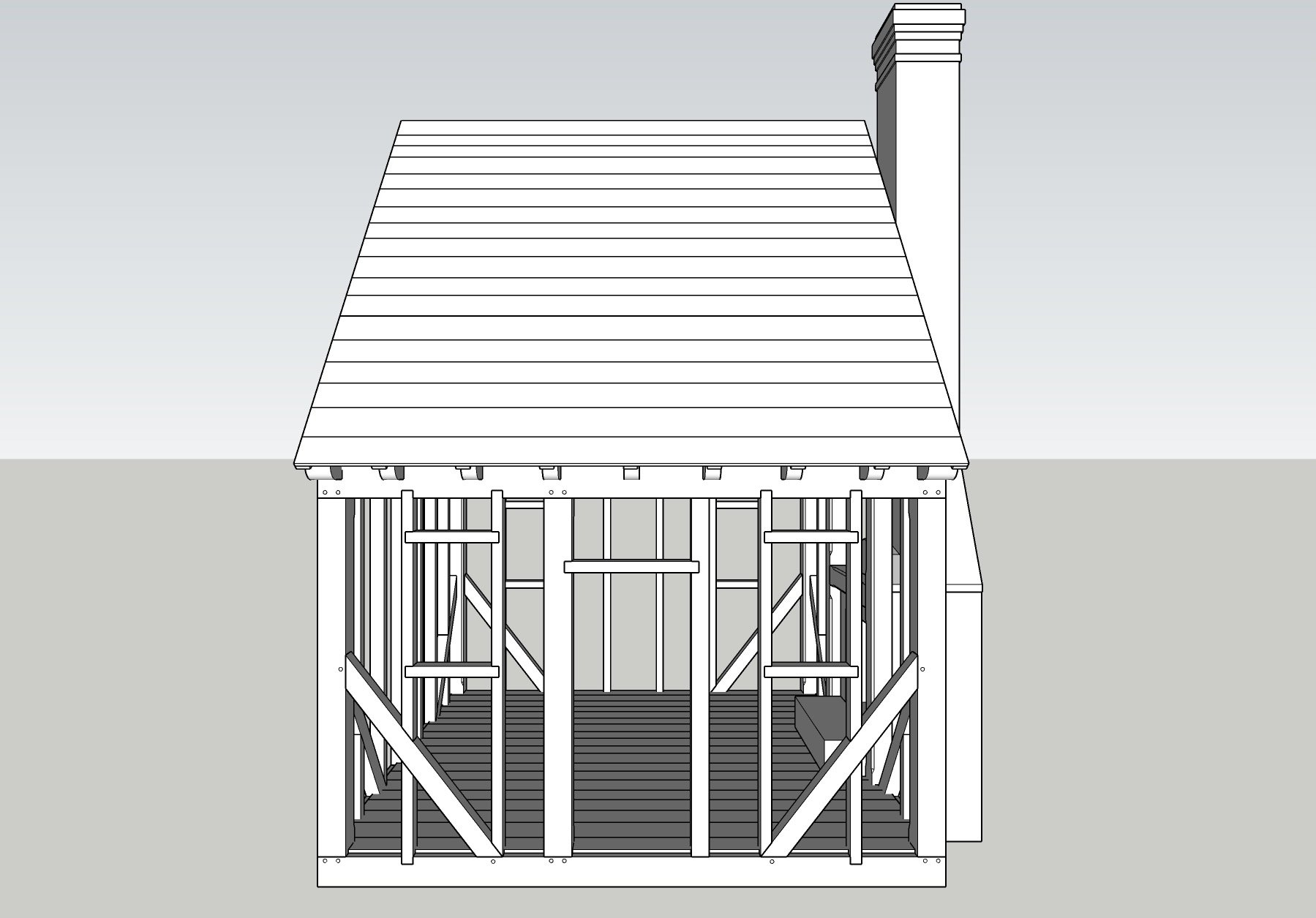

Virginia House Study Detail, by Diana Lorence

QUOTATIONS

”For the straight way was lost to me. . .” Dante, Inferno, Canto I

”There are moments when we all. . . “ Karen Armstrong, A Short History of Myth

”Let us build altars. . .” Ralph Waldo Emerson, The Conduct of Life, “Fate”

”And all shall be well. . .” Dame Julian of Norwich, Revelations of Divine Love c. 1393