Raising the last rafter pair into place. Pictured here from left to right are Josh, Matt, Harold, Madeleine, Nick, Kenneth, Ayinde, Jack, and Bobby.

To bent or not to bent, that is the question. Or anyway, that was the question last week when the rafters were raised on our Virginia House.

Like all such events, our roof-raising was a communal affair. All the carpenters and brickmakers were present—Matt, Jack, Bobby, Ayinde, and Harold, Josh, Kenneth, Nick, and Madeleine—each taking part in the lifting and placing and leveling. There is something about raising a roof that brings a community together and lifts the spirits. It was an altogether high-spirited occasion.

In the heat and action of it all, as I watched one rafter peak after the next take its place against the sky, project carpenter Matt Sanbury directed that the middle rafter pair, number five of nine pairs, should be set 3/4” forward of all the others. This passed mostly without remark. Except, I am ashamed to say, from me. The anomalous placement introduced an irregularity into the rising line of timbers that my tailor’s eye could not not see. After a thirty-year career that rose or fell over eighths of an inch, I can see 3/4” from thirty paces. That is how the whole Hamlet thing began.

Really, it began almost fifty years ago. I was a seventeen-year-old high school senior in a class on English literature, taught by Mr. Larry Minard. Heaven knows how I landed there. Before that moment, I can truly say I had no interest at all in studies. I had somehow succeeded in passing through eleven grades while remaining almost entirely oblivious to literature and languages, science and mathematics, history and civics and just about anything else you could put a name on that sounded even remotely academic. You name it, and I didn’t know it.

Then I encountered Shakespeare. This changed everything for me. Everything. There is nothing remarkable in that, I know, except perhaps for its night-and-day suddenness. I am only one among millions. But in my case, Shakespeare leapt like streak lightening straight across the sky to Homer and Aeschylus and Plato and Euclid, to Virgil and Vitruvius, Lucretius and Plutarch and Marcus Aurelius, to Dante and Leonardo, Palladio and Bacon, to Milton and Bach and Newton, to the Vedas and the Bhagavad Gita, to Confucius and Mencius, Lao-Tzu and Chuang Tzu, to Lady Murasaki and Kenko and Basho, to Avecenna and Averroes and Attar, to Hafez and Rumi and all the rest. All I had to do was watch the sky.

King Lear came first, which Mr. Minard introduced with that overpoweringly bleak film adaptation featuring Paul Scofield as Lear. I almost could not breathe while watching it. Then we read Macbeth, and finally Hamlet. For me, those plays fell into place and locked like struck timbers in the forming frame of my adult mind, to make a permanent reference point in my life. From that hour to this, without any conscious effort to do so, I have measured every aspect of my whole life from that conspicuous high peak.

Mr. Larry Minard in 2019, still an honored teacher after fifty years.

I blame dear Mr. Minard for all this. He was as mild-mannered and reasonable a gentleman as one might ever hope to meet, occupying a moment in his students’ lives when mildness and reason were hormonally least accessible. This, I think, was his genius as a teacher. He presented himself almost transparently, so that the literature he introduced to us should play out before our eyes as plain and powerful as life itself, wearing all the common garb of our tragic teenage passions.

I had not thought of those days for a long time before last week. Matt and his high principles brought it all back to me. Before last week, I did not really understand what a “bent” means in a timber frame, or why it is important. I never asked myself “whether ‘tis nobler in the mind” to bent or not to bent, in principle or in fact, at any extremity of the timber framer’s art.

In my Shakespeare-intoxicated, half-timbered imagination, a bent was one of those wonderfully bending timbers you cannot help admiring in pictures of jolly old Stratford-upon-Avon. Not so, it seems. Those are called “crucks.” The term cruck, or crook, comes from the Middle English crok(e), from the Old Norse krāka, meaning "hook". It shares its origin with the word "crooked.” A cruck frame commonly pairs symmetrically curving timbers that meet in a ridge at the top of a building, bound together with horizontal tie beams.

Anyway, enough about crucks. Back to bents. A bent, as it turns out, is an independent construction in a timber frame that can effectively be raised from horizontal to vertical all as one piece, continuous from floor to roof peak. It gives unity and rigidity to the frame. The term “bent” goes back to the past tense of an early Germanic verb “to bind,” referring to the way the timbers of a bent are joined together. The Dutch form is bint, the modern German word bind. The framing elements that constitute the end-walls or “gables” in a timber frame are bents. Oftentimes, intermediate bents are introduced between one gable and the opposite gable. So long as they act as an entire cross-sectional system of support from floor to post to peak, they constitute a bent.

Now, our small, single-room Virginia Frame requires only two structural bents, the two gable ends. These each stand in their own plane, with all their structural elements—sill, posts, studs, end-girts, rafters, and tie beams—justified to the outside of the building as one flush, flat wall. So far, so good. At this point, we pause for a brief chant from the chorus, entitled The Timber Framer’s Lament.

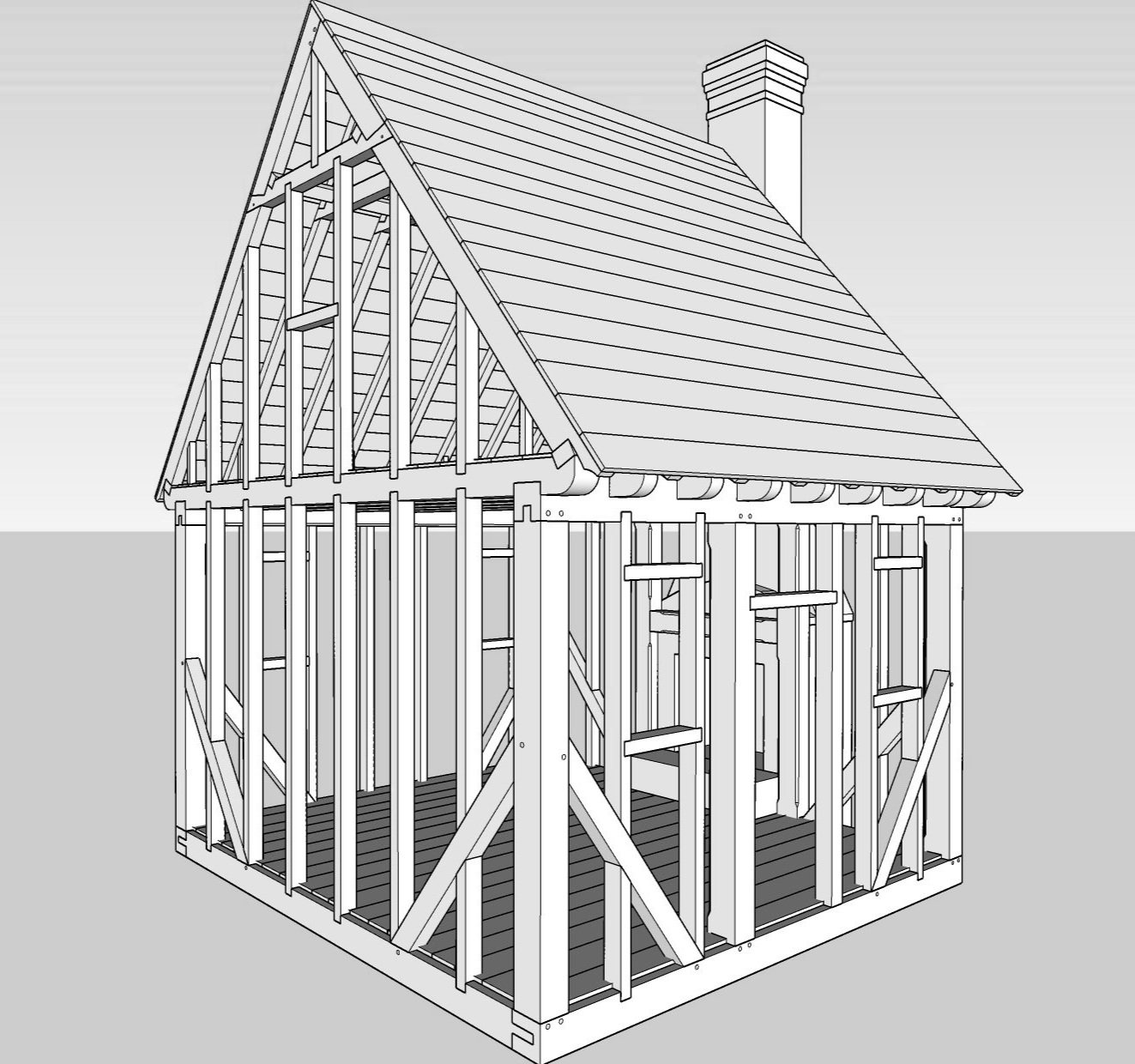

The Virginia Frame assembly from bottom to top: sill beams, posts and braces, studs, wall plates and end-girts, tilted false plates, loft joists, rafters, tie beams, and purlins.

Most timber frames rest on “sill beams.” The sills are the big, heavy, horizontal beams that rest either directly on the ground or on a foundation. Jointed into the sills are smaller but still stout “joists,” the horizontal members that support the floor. Rising from the corners of the sills and at principal openings like doors and the hearth, are “posts.” These vertical members support the structure. Supporting the posts are diagonal “braces.” Spaced at intervals between the posts are “studs,” lighter vertical members that give a surface to the walls. As you follow the posts and studs upward, they terminate in a sort of second sill that supports the roof, called “plates” at the front and back, and “end-girts” at the gable-ends. On top of the plates and girts rise the “rafters,” set at varying degrees of the diagonal to form the roof. Those rafters are then bound together by horizontal “tie beams” (or “collar ties”) to form a pair of rafters, and, from pair to pair, by horizontal “purlins.” In our very special case, there is also the identifying feature of the Virginia Frame, the “tilted false plate,” to which we shall return another day.

The timber-framer is called upon to somehow calculate and cut and join that forest of variety into one simple, interlocking whole. To further complicate the plot, if he is using band-sawn and “wany” timbers, as we are, the dimensions and shape of even the same kind of elements, say, the rafters, are going to vary from one to the next. The final twist is that many individual timbers are themselves twisted. Every reader of Shakespeare knows all about that. A single timber may wear the tragic mask of noble nature on one side, the comic mask of dent and wane on the other. “The time is out of joint: O cursed spite / That ever I was born to set it right”!

In order to set all that irregularity to rights, you’ve got to start somewhere. You’ve got to have some one common point of reference, something a little righter than the rest by which to navigate your way through a timber framing project. How often have I seen Matt contemplating the frame, calculating this or that relation and checking it against his charts, as though he were peering through a sextant at the stars. In a perfect world, perhaps such compromises and approximations would not be necessary. In this world, it is the nature of the tragic art.

All traditional timber framers must learn to navigate this dark territory. We all of us live mostly caught up in the comedy and farce of everyday chance. In the architectural arts, however, the master builder is perpetually engaged at a high edge where the material and the ideal meet. The timber framer’s art lies in traveling the edge between the weight and wobbliness of material nature and the abstract perfection of the geometric ideal.

That begins with the bents. Everything is measured from the uniform flatness of the bents at their outward edges. Then each particular thing is measured and placed according to its own best edge, called the “arris” (rhymes with “Paris”). I thought I knew what a bent was, at least before I woke from my half-timber dreams. I had no idea what an arris was until Matt enlightened me. The word is an alteration from the earlier French word areste, meaning “sharp edge.” It is related to arête, meaning “sharp mountain ridge.” An arris is an edge where two planes meet, as any one of four edges in a rectangular timber. Among carpenters, it is the leading edge of a timber, the “best” edge: the straightest, the truest, the cleanest edge. All measurements to establish position and relation in a timber are taken from the arris. Trees are not dimensional lumber and timber frames are not Platonic solids. An arris allows for all manner of imperfection by seeking out a single point of reference, chosen for its nearest approach to regularity.

Now, in the world of flush framing, which extends from 18th century Williamsburg to our day, that would be an end to it. All a flush frame has to do is support and shape the surfaces that wholly conceal it behind flat floors and walls and ceilings. But ours is not a flush frame. It is that very special, wholly American, modestly proud, elaborately simple, dressed and exposed phenomenon of the rural 17th and 18th centuries called a Virginia Frame. That means that Matt had to examine and position every last timber, not only with the arris of measure and truth in mind, but also with respect to the face of beauty. That is what a careful craftsman would have done in the period.

But, as happened for us in many cases, the truest edge does not always correspond with the most beautiful face. Alas that is so often the case in life! So, oftentimes Matt would choose to face the arris edge to the west toward the dark back of the house and turn the prettiest face forward toward the light. Which was quite right, but it considerably complicated relationships. I said a while back that timbers are not all of one size. Well, of course they’re not. But in our case, further complications arose from the fact that the ceiling joists that support the loft floor, and the rafters that support the roof, are not the same thickness. The joists are 3/4” thicker than the rafters that rest directly on top of them. So—what?

The what is this: since you justify the side of each rafter to the side of its joist, and the joists in our case are thicker than the rafters, you have to choose which side of the joist you justify the rafter to, forward or back, east or west. And, of course, you choose the regular side, the arris, which, in our case, mostly proved to be the back side. So, for uniformity’s sake, you justify all the rafters to the back side of the joist. That too is perfectly proper, and “saves the appearances.”

Except when it came to the fifth and central rafter. That central rafter marks the outside edge of the half-loft, which formed, in Matt’s mind, a kind of third bent. So that one-and-only rafter had to be justified to the terminal front edge of the loft joist, not to the back edge, putting it out of joint with all the others. Let’s not exaggerate. We are only talking about 3/4” in one rafter pair among nine pairs in a twenty-foot roof. Certainly it’s a tall roof, but we are not talking about high tragedy. Still, I have my tailor’s eyes and Matt has his timber framer’s principles, and where the senses and the mind cannot agree, at least a little tragedy is always waiting in the wings. “Ay, there’s the rub.”

But upon deeper examination, our friendly disagreement rose to a higher plane. Not of steeper dispute, but of more abstract conception. As we discussed the situation while waiting for a long rain to run its course, it became clear that Matt’s principled stand on the position of rafter five had more of Euclid about it than any consideration of mere utility. In fact, the end of the loft did not constitute a bent in any structural sense, for it was not continuous with any posts that communicated directly with the floor, nor could it be raised in one piece. Matt’s bent was more the dimensionless plane that lay as the Ideal Form behind all actual bents. It was the Platonic Bent he felt most strongly about, by the measure of which, all actual bents are mere shadows on the wall of a cave.

Project Carpenter Matt Sanbury practicing the precision he preaches.

Well! That is a carpenter I can understand. Matt is a thoroughgoing professional, and would not like to have his craftsman’s conscience confounded with Shakespearean tragedy and Platonic Forms and all my other literary eccentricities. I am only talking to myself, really. And possibly to Mr. Minard across the years.

As soon as I understood the meaning of Matt’s principles, we were able to arrive at a mutually satisfactory solution. We would leave rafter five where Matt had put it, and budge rafters two, three, and four, six, seven, and eight, all 3/4” forward to the east. It would not take long, the arrises would have served their purpose in truth before bowing to beauty, and all bents would be set straight to the sky.

To bent or not to bent is no longer the question. In this imperfect world, it is the striving that matters. The only bents beyond question are the bents in our mind.

Yours always,

Michael

The Innermost House Foundation is an entirely volunteer organization

dedicated to renewing transcendental values for our age.

IMAGES

M. Lorence: Raising the Roof, February 3, 2022

EICC: Mr. Larry Minard accepting an award as Outstanding Adjunct Instructor of the Year, 2019

Jeffrey Klee: Virginia House isometric drawing, December 2021

D. Lorence: Mallet and Rafter Tail, February 3, 2022

Jerry McCoy: Matt Sanbury notching a purlin, February 8, 2022